14th March 2018

Mike Ingram unpicks the role of Northampton in the Barons’ War and how it played a key role in bringing King John to seal Magna Carta…

In 1202, Northampton was one of eleven towns which purchased the right to buy and sell dyed cloth from King John. It soon had a national reputation for fulling and dying cloth with 300 cloth workers by the fourteenth century. The town was also a major trading centre for corn and horses and where roads such as Horsemarket and Marefair got their names.

It was also at this time that Northampton was granted its first Mayor. On 17 Feb 1215, whilst King John was hunting at Silverstone, he informed his ‘good men’ that he had accepted William Thilly as mayor of Northampton and that they should elect twelve more discreet and better of the town to despatch with him their affairs in the town. It was a special privilege and one of the very first Mayoralties in England. Also unlike the Richard I’s charter, which was in effect sold to the town to raise funds for his crusade (the liberties which it granted were actually in place before 1185), John’s charter seems to have been enacted to strengthen the town’s support for him as the dispute with the Barons intensified.

At the beginning of January 1215, the discontented Barons met John in London. John, playing for time as always, asked that he might have until Easter to consider their demands and arranged to meet them again at Northampton on 26 April. However, as soon as the meeting ended, John began to raise a mercenary army. He also wrote to the Pope, shrewdly offering to go on a crusade, thereby gaining special papal protection.

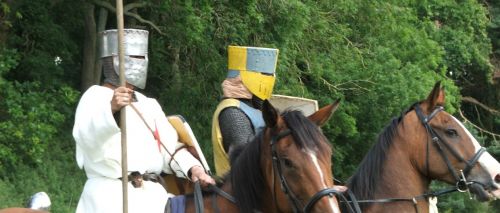

Concerned over John’s warlike preparations and Papal support, the Baron’s assembled an army at the Stamford tournament field near Peterborough during Easter week (19-26 April). Five Earls and forty Barons, mostly from the north, are mentioned by name as being present at the muster,” with many others”; they all came with horses and arms, and brought with them “a countless host,” estimated to comprise about two thousand knights, plus other horsemen, sergeants-at-arms, and foot soldiers.

From Stamford they marched to Northampton, and on finding John not there, marched on to Brackley. John sent William Marshal and Steven Langton to obtain a list of their demands. They met with the Barons on 27 April, who “presented to the envoys a certain schedule, which consisted for the most part of ancient laws and customs of the realm, declaring that if the king did not at once grant these things and confirm them with his seal, they would compel him by force.” It was this list of demands that would eventually become the Magna Carta.

Langton and the Marshal returned to the king, now in Wiltshire, with the list of demands. One by one the articles were read out to him by the Archbishop. According to Roger of Wendover, after he had heard them all John said “Why do these barons not ask for my kingdom at once ?… their demands are idle dreams, without a shadow of reason” Then he burst into a fit of rage, and swore that he would never grant to them liberties which would make himself a slave. He then sent the two back to the Barons and instructed them to repeat his words verbatim. On hearing this, the Barons immediately renounced their fealty to the King and chose Robert Fitz-Walter as their leader, to whom they gave the grandiose title of “Marshal of the army of God and Holy Church“. They then marched back to Northampton, occupied the town and laid siege to the castle. However, they had not brought any siege equipment and after two weeks, were forced to give up, but not before many had been killed including Fitz-Walter’s standard bearer. The Barons then moved to Bedford where William de Beauchamp readily gave up his castle and then on to London, which they reached on 27 May. In the meantime, the townsfolk of Northampton rose against the garrison of the castle, killing several of them. In retaliation, the garrison charged into the town, killing a number of townsfolk and setting houses on fire.

With London under baronial control, John knew he was beaten; and sometime at the beginning of June, he sent William Marshal to the Barons saying “…that for the sake of peace and for the welfare and honour of his realm, he would freely concede to them the laws and liberties which they asked ; and that they might appoint a place and day for him and them to meet, for the settlement of all these things.” A meeting was arranged where John would agree to the Barons demands. The meeting was set for 15 June, and the place, a meadow between Staines and Windsor called Runnemede.

So that’s the story of how the Magna Carta came to be sealed. One of the most important events in English history: Yet, look around you and you will see little or no or mention of Northamptonshire’s part.

It was also at this time that the Sheriff of Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Cambridgeshire, Faulkes de Bréauté became one of John’s leading supporters. Few today will recognise his name, yet he has become part of our daily lives.

Little is known of his early life except he was born of common stock in Normandy, and was often referred to only by his first name, which legend says, was derived from the scythe he had once used to murder someone. He began his military career as a mercenary in King John’s army but first comes into public view in 1206, when he was sent on royal service to Poitou by the King. Upon his return in February 1207, he was entrusted with the wardenship of Glamorgan and Wenlock, and around that time he was also knighted. He was then made constable of Carmarthen, Cardigan and the Gower Peninsula, and gained a fearsome reputation in the Welsh Marches, destroying Strata Florida Abbey in 1212 for its opposition to the king. In recognition for his services, De Breauté was made King John’s steward at the beginning of 1215.

On 28 November 1215, de Breauté captured the nearby castle of William Mauduit at Hanslope in Buckinghamshire, and then Bedford Castle which belonged to William de Beauchamp, which he was allowed to keep as a reward. The desperate Barons, offered the English throne to Prince Louis of France early in 1216. Louis landed on 19 May and quickly took control of London. De Breauté was tasked with defending Oxford against the baronial forces. On 17 July he and the Earl of Chester sacked Worcester, which had allied itself with Louis. In reward John gave de Breauté the hand of Margaret the daughter of Warin Fitzgerald, the royal chamberlain. She was the widow of Baldwin de Revières, former heir to the Earl of Devon, who had died earlier that year, and until her son was old enough to take up the Earldom, De Breauté was effectively equal to an earl. As Margaret’s dowry he gained control of most of the Revières lands and manor’s, including the Isle of Wight.

One of the properties in South Lambeth, London he gained on his marriage was a hall close to the Thames. It soon became known as Faux’s Hall. Over time this was corrupted to Vauxhall. And just over six hundred years later, the Vauxhall Ironworks were founded close by. In 1903, they built their first car and adopted de Breauté’s griffin badge as their own.

When John died on 19 October 1216, de Breauté served as the executor of his will, and was one of the royalists who reissued Magna Carta on 12 November. Under Henry III, de Breauté continued to fight with the same loyalty he had shown John. Many of the other barons changed sides to support the new king. On 22 January 1217, de Breauté and his men committed their worst atrocity, attacking St Albans because he believed it had come to terms with Prince Louis, although it had done so under duress. After attacking the town, he turned on the abbey, killing the abbot’s cook and only leaving after blackmailing the abbot for 200 marks. His men also attacked Wardon Abbey, and although he eventually compensated St Albans it was felt he only did so to please his wife.

At the end of February 1217, de Breauté led a royalist force in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the port of Rye. After this, he captured the Isle of Ely, then joined Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester to besiege Mountsorrel castle, north of Leicester. On 20 May 1217, de Breauté joined William Marshal, 400 Knights, 250 crossbowmen, and a larger auxiliary force of both mounted and foot soldiers who had assembled at Northampton, to break the siege of Lincoln. The royal forces beat the rebels at Lincoln and soon after Prince Louis returns to France.

In reward for his part in the victory at Lincoln, the King and the royal court celebrated Christmas 1217 at Northampton at de Breauté’s own expense. On St. Stephen’s day, all the King’s enemies were excommunicated and the barons were forced to come to Northampton to surrender their castles. However, de Breauté and a number of the barons refused. Because of his status as a commoner, de Breauté’s position was more tenuous than that of his enemies and he increasingly relied on the favour of noblemen such as the Earl of Chester and Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, who supported him due to their disenchantment with the new regent, Hubert de Burgh.

In June 1220, William de Forz, the Earl of Aumarle, who was described as “a feudal adventurer of the worst kind” refused to surrender Rockingham Castle which he had made the centre of his power base. De Breauté was ordered to take it by force and lay siege to the castle for a week with “rams and catapults and all the engines of war then in use”. When the castle finally surrendered after a surprise assault, only three loaves were found left in the place.

During the following January, the Earl of Aumarle seized Fotheringhay castle. It was poorly garrisoned, and helped by a frozen moat, he attacked it on all sides, setting fire to the door and killing two soldiers. They then ravaged the county in all directions. The King, summoned all the magnates and all the armed forces they could raise to Northampton, who then took it back by force. Aumarle fled, but was excommunicated by the Papal legate and 10 bishops.

In November 1223 tensions began to boil over again. De Breauté, and the Earls of Aumarle, Chester and Gloucester attempted to seize the Tower of London. De Burgh and the king were forced to flee to Northampton. A new civil war was only averted by the intervention of Simon Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, but after a peace conference in London on 4 December failed to reach agreement, tensions rose again. Langton threatened to excommunicate the “schismatics” as they had become known, if they failed to return to the king’s court. Finally, on 30 December, they agreed to give up their castles and shrievalties to the king. De Breauté immediately lost Hertford Castle and the shrievalties of Oxfordshire and Northamptonshire, and lost the rest of his shrievalties by 18 January 1224.

A month later, de Breauté was ordered to give up Plympton and Bedford Castles. De Breauté refused. In the spring of 1224, three justices found him guilty of 16 counts of Wrongful Disseisin or appropriation of other men’s land, heavily fining him. De Breauté was outraged and ordered his brother William de Breauté to seize the justices at Dunstable. Two managed to evade their clutches but on 16 June, they seized Henry of Braybrooke, and threw him into the dungeon at Bedford. Distraught, Braybrooke’s wife went to the King who was at Northampton discussing the defence of Poitou. When de Breauté refused to give him up, the King marched on Bedford castle. Siege engines were brought from Lincoln, Northampton and Oxfordshire, while carpenters built others on site using timber from Northamptonshire. 43,300 crossbow bolts are known to have been ordered by the king and stone quarrying provided ammunition for the siege engines.

Finally on 15 August, after using every known siege technique, the King’s army broke into the castle, and William and the garrison surrendered. Near contemporary accounts suggest that the prisoners asked the Archbishop for assistance, but it was declined. Henry was in no mood for mercy and wished to make an example of them. Then, except for three knights who agreed to join the Knights Templar, the King had all eighty surviving male members of the garrison, including William, hung. Three days after the fall of the Castle, the King received a letter from the Pope demanding that Henry cease his campaign against de Breauté.

After the fall of the castle, Alexander de Stavenby, the Bishop of Coventry, convinced de Breauté who was in Wales to surrender. At Northampton, on 25 August 1224, de Breauté pleaded forgiveness from the King, handing over his last two remaining castles at Plympton and Storgursey., Falkes officially gave up his lands, and chose exile to France rather than judgment from the barons. Arriving in Normandy he was imprisoned by Louis VIII in Compiègne as revenge for his defeat of the French forces during the war, but was released in 1225. En-route for England, de Breauté was captured in Burgundy by an English knight he had once imprisoned, but was released after papal intervention. De Breauté then spent some time in Troyes, but was expelled from France in 1226 for refusing to pay homage to the king. He returned to Rome, but died soon after, allegedly from a poisoned fish.

Reference: NeneQuirer

Your login details have been used by another user or machine. Login details can only be used once at any one time so you have therefore automatically been logged out. Please contact your sites administrator if you believe this other user or machine has unauthorised access.